Can the Market Get High on its Own Supply?

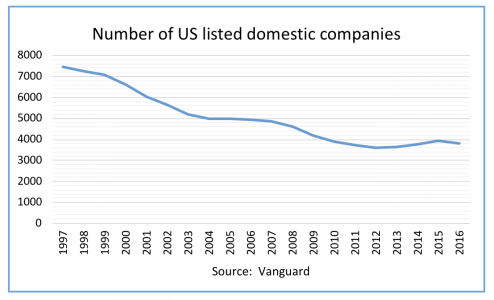

How many companies are in the Wilshire 5000—a broad index of publicly traded domestic stocks? On the surface, this appears to be a brain teaser akin to “what color was Napoleon’s white horse?” The answer, however, may surprise: 3,492 as of December 31, 2017. In fact, there have been fewer than 5,000 stocks in the index, named for its breadth of coverage, since the end of 2005. While there has been more attention given to the demand side of the stock market, very little has addressed the supply side, which has undergone a steady, stealthy shrinkage over the past two decades. According to Bloomberg News, there are now more indexes than publicly traded U.S. stocks due to the surge in popularity of exchange-traded funds (but that is a topic for another day).

Reasons for the decline in stocks

There are many reasons for the sharp fall in the number of listed equities. Consolidation via merger and acquisition activity, although cyclical, has been robust over the period. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 and subsequent ramp up of its manufacturing base has made it cheaper to produce goods overseas, leaving domestic companies less in need of investment capital. The regulatory burden of being a public company has grown substantially with the passage of laws such as Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank. In the post-financial crisis era, savings have been abundant, allowing companies easy access to private sources of capital. Company founders have also pushed back against the loss of control and pressure to emphasize short-term financial results that are associated with being public.

The decline in the number of publicly traded companies is just one side of the coin. Companies still listed have also reduced their aggregate share count, further pressuring supply. According to Yardeni Research, the number of outstanding shares in the S&P 500 (adjusted for stock splits and stock dividends) has fallen by more than 7% over the past six years.

Should we expect higher prices as the norm?

We know that if the supply of a good falls, its price will rise if demand remains unchanged. Given that the supply of publicly traded equities has dwindled so dramatically, it would follow that the equilibrium (or mid-cycle) price of the remaining stocks should be higher than in the past, holding other valuation factors (earnings, discount rate) equal. In other words, investors should be willing to pay something of a scarcity premium to retain access to domestic equities. Bolstering this line of thought is a report by Mauboussin, Callahan and Majd called The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks that states:

listed companies today are on average larger, older, and more profitable than they were 20 years ago. Further, they operate in industries that are generally more concentrated. The overall size and maturity of listed companies means they are more likely to pay out cash to shareholders in the form of dividends and share buybacks than companies were in the past.

We think that there is a strong case that domestic equities will command commensurately higher full cycle valuations. While it’s always dangerous to judge market valuation at a single point in time, perhaps the current market is not as overvalued as it might appear when compared with historical measures. It could also mean that past valuation relationships between U.S. stocks and other asset classes may be less reliable as well.